Why Students Study Hard but Improve Slowly

The Hidden Reason Secondary School Students Feel Stuck No Matter How Hard They Try

(Advice from an Oxford graduate from HCI)

Here’s something that doesn’t get said enough.

A lot of kids aren’t under-working. They’re overworking. Wrongly.

If you’re a parent, you’ve probably seen it play out at the dining table or behind a half-closed bedroom door. Your child is seated. Books open. Notes everywhere. Highlighters uncapped like weapons. Hours go by. And yet—when results come back—nothing really changes. Or worse, they creep up by half a grade and stall. Again.

Frustrating, isn’t it?

I don’t think this happens because students don’t care. It’s the opposite. Most care deeply, sometimes too deeply. The real issue isn’t effort, but method. Not a lack of discipline, but a lack of direction.

A tale of two study cultures (and a rude awakening)

I came up through Singapore’s system. Hwa Chong Institution. Top 10 in school. Eight distinctions at graduation. I did what “top” students do: long hours, thick notes, repeat until exhaustion. It worked—up to a point.

Fast forward to my time at Oxford.

I now read Economics & Management there and sit in the top 10% of my cohort. I’ve also been fortunate to receive the PSC Open Scholarship and the SAF Overseas Scholarship. But here’s the part that caught me off guard: almost nobody studies the way we were taught to study back in Singapore.

No marathon mugging sessions. No endless rereading. No rewriting notes just to feel busy.

Instead? Short bursts. Intense focus. Active recall that’s uncomfortable. Quiet, almost boring reviews of mistakes.

That contrast bothered me at first. Then it I understood:

Studying more is not the same thing as learning better. In fact, sometimes it’s the opposite.

What parents are actually noticing (even if they don’t phrase it this way)

When parents say things like:

“My child studies every day, but grades won’t move.”

“They tell me they understand, but exams say otherwise.”

“They memorise everything… and still can’t apply.”

What they’re seeing isn’t laziness. It’s passive learning in disguise.

Being busy doesn’t mean being effective.

The big misunderstanding: reading feels like learning (but often isn’t)

This is the quiet trap.

Students assume that because something looks familiar on the page, it must be stored in the brain. It isn’t. Recognition is cheap. Retrieval is expensive. Performing well in exams demands the latter.

Reading notes again and again feels like you’re making progress. But the brain hasn’t been challenged, so it hasn’t adapted.

No friction means no memory.

Three habits that look responsible — but actually break progress

Rereading notes

It’s easy - anyone can do it! That’s why students like it. Unfortunately, the brain goes on autopilot, so very little of what you read actually sticks.

Copying or rewriting notes

Rewriting notes in neat handwriting seems like a productive use of time. But the mind? Half-asleep. Copying trains your wrist, not your thinking.

Practising questions without post-mortems

This one is sneaky. Sometimes I see my juniors do full practice papers, feel productive, move on. But without reviewing their mistakes, students will never learn and improve!

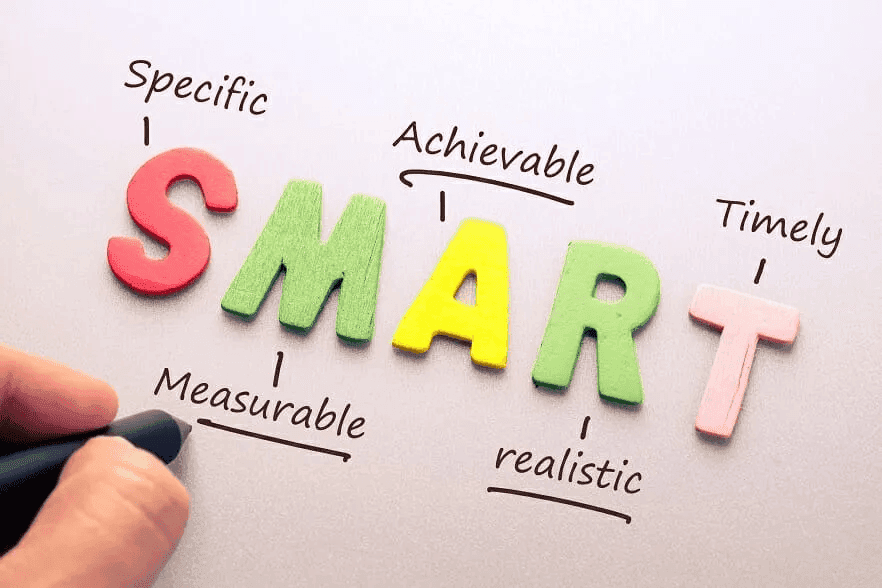

The shift that actually moves the needle

At some point, students have to stop asking, “How long did I study?”

And start asking, “What changed because I studied?”

Learning accelerates when students move from passive exposure to active processing.

Retrieval. Explanation. Correction. It’s harder, and definitely more annoying. But it works.

If I had to pick one habit: the mistakes journal

If there’s one thing I’d insist on—gently, but firmly—it’s this.

Every student should keep a mistakes journal. One per subject.

Every time you make a mistake, you should log it as an entry in your journal.

Each entry answers three things:

What went wrong?

Why did it go wrong?

How can I prevent myself from making this mistake again?

Here’s the important part: these mistakes are reviewed daily. Even for ten or fifteen minutes when you’re unwinding.

I do this even now when I’m in Oxford. It is truly uncomfortable to sit with your mistakes and be painfully aware of where you’re lacking. But if you do it every night, you’ll start to improve exponentially.

Where parents fit in (without becoming the study police)

This part is delicate.

Parents help most when they stop equating time-at-desk with progress. Sitting is not studying. Silence is not learning.

A better question than “How long did you study?” might be:

“What mistake did you uncover today?”

That question nudges reflection instead of compliance. It changes the tone. Less pressure, more thinking.

A quiet truth, before I go:

Singaporean students are rarely short on effort. What they’re often short on is feedback and strategy.

When students learn how to study—really learn—something odd happens. They often study less. And get better results anyway.

Efficiency compounds. Early.

And that, often, is the real advantage.